Last week, a buddy of mine drove up from way out in the boonies of Illinois so we could go see an art exhibition he saw advertised on TikTok, called The First Homosexuals: The Birth of a New Identity, 1869-1939. Let’s talk about that!

If you are in or around Chicago, you can get tickets at the link until the end of July, if there are any left. They’ve asked to show it other places, and Chicago is the only city to say yes. It’s worth going, if you can— the art is very good.

The gallery’s works-on-display extend before and after its stated timeline, but these years are chosen very intentionally. 1869 is meaningful because it’s the year that the terms “heterosexual” and “homosexual” were coined by Karl Maria Kertbeny, which the gallery effectively credits with the invention of homosexuality as an identity— as in, a thing that you are, rather than a thing that you do. Karl Heinrich Ulrichs (a totally different Karl from the generation before, arguably Europe’s first gay activist) had written this sort of identitarian defense of homosexuality at least five years earlier, but his version was explained through a theory of homosexual essence— that gay men and women were born with opposite-gendered souls, which motivated both their gender expression and sexual behavior. This was later termed “inversion” and reframed as a medical pathology by Richard von Krafft-Ebing in his Psychopathia Sexualis (1886), rationalizing homosexual behavior as a syndrome rather than a sin.

All of these attempts to create a homosexual identity were expressly political— Ulrichs and Kertbeny were writing pamphlets with legal and philosophical arguments against the criminalization of sodomy, which was ramping up in their various Germanic states at the time. Kertbeny was more agnostic on the whole “born this way” narrative—he argued that it was none of the state’s business whether homosexuality was innate or not, because it simply wasn’t immoral either way— but he stands out because, in his attempt to create a more liberating language, his framework was used by later medical institutions to legitimize a different kind of homophobic policy: the pursuit of a “cure.” The invention of homosexuality, then, was entwined with the invention of homophobia, which then became one of Europe’s colonial exports.

Gay people did not fare well through any of this. 1939 represents the start of WWII, the end of the Weimar era and the beginning of the Nazis’ genocidal project. Whatever queer public life had been built in Germany from the mid-1800s had by that point been systematically extinguished by criminalization, raiding gay bars and burning publications, exiling its important peoples and allies and incarcerating the intersectional poors.1

All these arguments and conceptualizations of gay identity came about rapid-fire in the latter half of the 19th C, and of course they were the background noise of people living their lives, fucking their friends and mentors, forming lifelong commitments, trying not to die in the war or on the street, and making art about it all.

On its face, the exhibition is articulating a kind of gay semiotics, showing the symbolism and imagery that the queers of yesteryear focused on and flexed as a nudge-wink to what they were up to in the hours they were not painting, and how those symbols changed alongside evolving philosophies of what it means to be gay. It is also trying to contextualize our current moment by showing us the art that was made and the people who made it in the cauldron of discourse that preceded us— the gallery is very clear that this is a political exhibition. In the brochure they give out at the gallery, they really don’t pull any punches:

Throughout the early history of the homosexual, as this exhibition demonstrates, same-sex desire and gender identity were twinned to the point of being inseparable; thus it is no surprise the rise of homosexual imagery also spurred the rise of non-binary or trans representation in its wake. Put otherwise, modern gay and trans identity were actually born together. It is our fervent hope this exhibition will aid in the reclamation of gender to the story of sexual difference.

Too often, we fall into the trap the invention of the “homosexual” laid out for us— perceiving sexuality as an unchanging essence of our being, something we are, not something we do. This exhibition instead begins by charting how “homosexuality” is in fact not an eternal category, but a historical one, subject, like all of history, to ceaseless change. For this reason, the exhibition ends with the destruction of much of what came before by the Nazis, at once a stark reminder, and for us today, a prescient warning, of the far-right’s profound hostility to human difference, which is to say, to life itself.

Put bluntly: they would like to challenge the contemporary gays who think that trans people are a horse of a different color. They are tracing the origins of the “born this way” narratives, pointing out that Nazis were great fans of that sort of essentialism which did not accurately reflect the complex realities of peoples’ lives, and implying that America’s own Weimar era (lol, lmao) may be facing its own imminent demise.

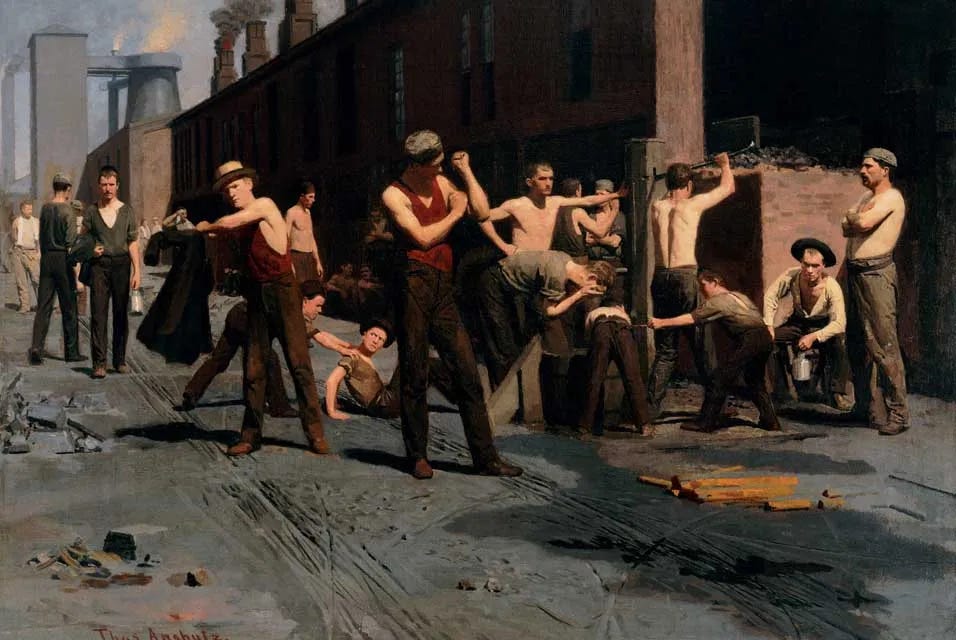

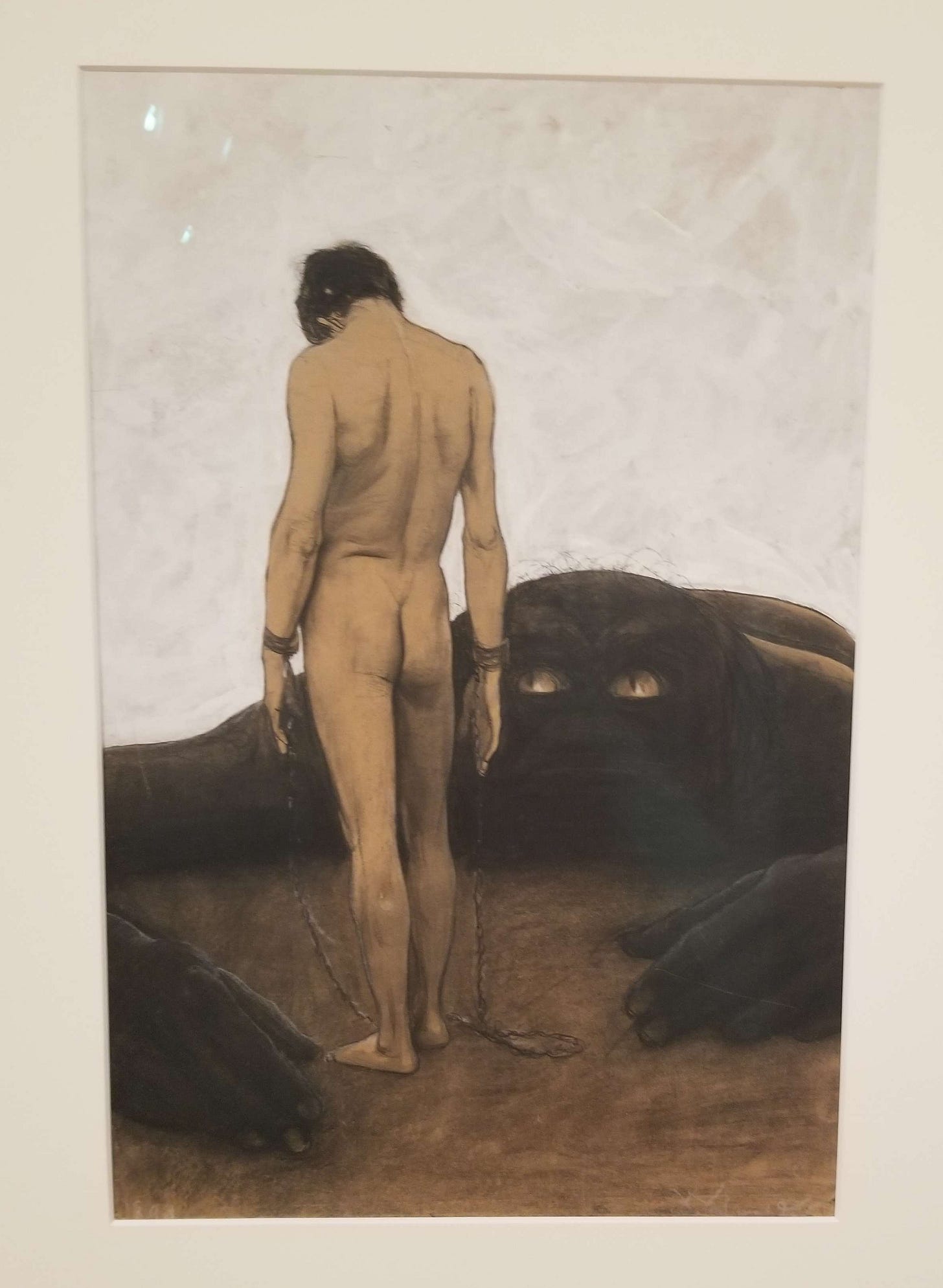

One section “chronicles a significant shift in homosexual representation never before noted— how and why homosexual artists overwhelmingly represented adolescents in the 19th century but then turned from youth to mature, hypermasculine figures around the turn of the century.” What they mean is that homoeroticism in art was often represented c1870-1900 via references to classical twinks2— lithe young Prometheus and Apollos and Davids, etc— but when the century turned, more art began to appear that eroticized virile adult men, with all their muscles and hair and belly fat and so on.

The implication in their timeline of homosexual identity is that Kertbeny and his contemporaries’ simultaneous affection for gender-essentialism and rejection of the feminizing implications of “inversion” theory rather uncomfortably dovetailed— or perhaps just prefigured— the Nazis’ obsession with the white masculine body as a perfect human specimen.

I should note that the gallery had pretty tight security. No bags allowed, no pens, metal detectors, timed-and-ticketed admission. They have braced themselves for backlash, and I don’t think right-wing homophobes are the only ones they’re worried about. They’ll outright call right-wingers profoundly hostile to life itself, but they’re mostly implicating us— gay & trans people—pressing us to develop a more nuanced and contextual understanding of identity, so as to resist our own destruction.

I think I love that? I didn’t know it until I wrote it, but I love that. It was a very good show.

BUT JESSE, WHAT ABOUT THE LESBIANS

Oh, there were lots of lesbians, on the gallery walls and during-the-era. I don’t have much to say about them aside from they were there, and they were beautiful, and they made lots of beautiful things. They had like four or five different Gerda Wegener paintings, and I’m fucking crazy about Gerda Wegener.

It seems a bit difficult to situate the gay lady artists in this context because the Nazis overwhelmingly focused on gay men. Women were not arrested or sent to labor camps for having sex with other women so much as they were prosecuted for cross-dressing, being “antisocial” or “political” (read: refusing to get married, demanding legal rights, etc). But this is another thing that I think the curators managed very well, focusing on women’s crossdressing as a point of political and philosophical solidarity— women who went butch faced legal persecution and intentionally expressed a gay identity, during a time when both homosexuality and gender non-conformity both represented a rejection of patriarchal control over their lives.

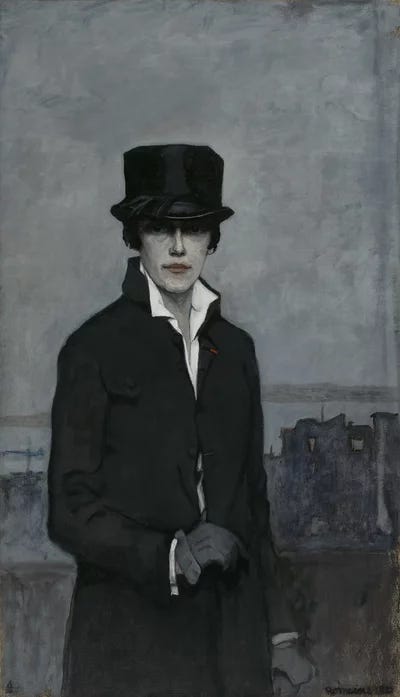

Romaine Brooks is a great example, a lesbian painter who married a gay man for British citizenship and then left him less than a year later— not only because he threw tantrums when she wore pants, but because he acted entitled to her inheritance. So the gallery makes a very clear case that same-sex attraction and gender-nonconformity have been so conceptually intermingled throughout our recent history that any attempt to starkly separate the two is destined to fail. Our understanding of gay identity is— has always been— so intensely wrapped-up in conventions of gender, binary and androgyny; in subversion, play, and redefinition of those conventions and their symbols. Trying to piece them apart is like trying to un-bake a cake, and— when applied to policy— is liable to pointlessly ruin a lot of peoples’ lives.

I’m being sort of coy here. Haha, gay man has nothing to say about lesbians, how predictable. But. I mean, okay. Let me see if I can explain this.

The night before we went to the gallery, we also went to a film showing at Facets Film Forum, who have been putting on a series of films related to the gallery show every Wednesday over the summer. The night we went was titled Gender Benders, where they showed three “crossdressing romance” comedies from the end of the silent film era— Charlie Chaplin’s A Woman, Julian Elting’s Madame Behave, and Ernst Lubitsch’s Ich möchte kein Mann sein. The last one surprised me because, judging by the titles, I thought I was going to see three films about male actors dressing up as women.

Ossi, who looks to be in her late teens or early twenties, is a disobedient tomboy— she smokes cigarettes, plays poker, sticks her tongue out at her governess, and throws candy from her windowsill to groups of boys who come to flirt with her. Before her uncle goes overseas for work, he hires a teacher to help keep her in line, a handsome man who instantly charms her governess and whose commands prove surprisingly compelling to bratty Ossi. Annoyed at her restrictive life at home, she dons a wig, a suit, and a tophat for a night on the town. Her little dress-up montage is interposed with shots of her teacher doing the same routine, on his way to the same party.

What follows are the recognizable tropes of budding transmasculinity. Women find Ossi impossibly cute and genteel, while other men are jealous of him for the same reasons. He finds that men have their own difficulties— their freedom comes with just as much preening and posturing, only no one is going to take care of you, give up their seat on the bus or apologize when they step on your toes. There’s a whole scene about the comedy of being unsure which bathroom to use, etc.

He finds his teacher trying to woo a lady at the party, and fights for her attention just to get back at him. When she flippantly rejects them both in favor of the next suitor’s attention, they steal a table to themselves and get drunk on champagne. On the cab ride home, they kiss.

I spent the full 45 minutes rapt at attention, except for when I was trying to surreptitiously record snippets on my phone of the haunting, jazzy electric guitar score Peter Maunu was playing from the front row. This reads to me as a depiction of bisexual homoeroticism, T4C circa 1918— until the last ten minutes.

Having drunkenly swapped coats on their way out the door and then passed out in the cab, the cabbie looks for their addresses in their coat-pocket business cards, and unwittingly drops them off at one another’s homes. Ossi wakes up in the morning with a hangover and cries, asks her teacher’s butler to blow her nose for her. When she goes back home and meets her teacher, he discovers her ruse, but is still attracted to her. Returned to her proper place as child, student, and future wife, she declares, “I don’t want to be a man!” Kiss, curtains, title drop, the end.

I missed the first third of Madame Behave because I was outside, having a cigarette and watching people walk by in the rain. I wondered what it was like to live in an era where masculinity was apparently so visually-androgynous that a woman-in-drag and a clean-shaven young man were indistinguishable in day-to-day life. I fretted about how rude it was, to interrupt everyone else’s viewing so I could leave two minutes into the next film, only to awkwardly shuffle back down the darkened aisle with another beer twenty minutes later.

It seems to retrofit a heterosexual explanation onto its plot: a well-to-do man of good prospects kissing a younger man isn’t doing anything gay— it’s just the transcendental hetero imperative piercing through Ossi’s facade. Ossi’s desire for freedom, expressed through her boy-drag, is ultimately framed as a childish one— which of course finds its limits in experiencing the hardships of being responsible for oneself.

So this is what I think of, when I look at art of butch women or other historical examples of “crossdressing” lesbians: it feels pointed that “female masculinity” is so consistently understood as a means, not an end, something which women do because it represents freedom— particularly freedom from men.

I feel such fondness and kinship with butches like Romaine Brooks, and with the particular way that a kind of masculine embodiment both solidifies our agency and makes it legible to other people, consequences be damned. But there is a stark divide between us in that I do this because I love men— I want to fuck them and look like them and be recognized by them as one of their own. That’s kind of my whole jam. My gender identity, if it is a real thing that must be named in the context of everyone else’s baggage, is more faggot than man. And by being a man— by drawing this line in the sand of my identity— I am separated from them, these butches that I love, mostly because they clearly want nothing to do with me.

That bit from the brochure keeps sticking with me. It is our fervent hope this exhibition will aid in the reclamation of gender to the story of sexual difference. The trap [of trying to understand queerness as] something we are, not something we do. I get what they mean, and I agree, but there is also a bitter irony in being a “masculine female” who isn’t, by strict definition, homosexual. It’s funny, I guess, to go looking for contemporary “transmasculine” “community” and find that most FTMs I meet are current-or-former lesbians, both obsessed with women and repulsed by men in a way that I wholly cannot relate to. It feels like a sort of cruel joke that contemporary trans fags like me— or at least, our aspirations— are more clearly reflected in the “ephebic” archetypes of yesteryear than in the same-bodied butches whose lives we would likely have lived if we were born a hundred years earlier.

A THING THAT YOU DO

Part of why I like looking at historical gay art is because it allows me to understand myself as a creature that exists in a certain time and place, but also as a part of something greater than myself and my brief time on this earth. The floor of the gallery dedicated to portraits and relationships was very moving to me because it grounds all of this contextual political-philosophy babble in the reality that these people were here, once. They were like me, even as they were very much not like me.

This century-old idea of gay identity serves as shorthand for both attending to our differences and offering a cultural lineage where literal lineages cannot exist. Gay people famously do not have genetic offspring, and I think this sort of spiritual family tree, which connects us through our principles and experiences— our creative imaginings of what a better world could look like and our depictions of the harsh world we must actually inhabit, different facets of a universally-human story of desire— refutes the genetic obsessions of the Nazis more strongly than any political pamphlet ever could.

I’m less interested in “minority representation” as a moral imperative— walking into a gallery expecting every frame to be a mirror— than I am in feeling connected somehow to the people, the extant humanity which makes life and culture into something real, something that matters beyond whether the picture on the wall flatters us or has pretty colors or whatever.

The last floor of the gallery was dedicated to gender-nonconformity more generally, and the early inklings of self-aware art by-or-about people we would today recognize as transgender. This painting, La Prostíbulo (The Brothel), shows a group of sex workers, including one who is recognizable as a trans woman. The contrast between her and her sister is remarkable— one dressed in black, posed carefully and conservatively, her sister lounging pinkly on the couch with a cigarette and and one tit hanging out. They both stare at us, one with plaintive dignity and the other with a sort of smug amusement, both daring us in different ways to fucking say something, why don’t you? go on, sport, tell me what’s on your mind, I fucking dare you. In front of them sits a birdcage, lending this piece its other title— La Jaula (The Cage).

This isn’t just a beautiful oil painting, or a rare depiction of a trans woman from 1926 (!!!), or a beautiful rare oil painting of a trans woman from the 20s who is also a sex worker— it’s an image of a trans woman’s mutual comraderie with the other women who share her life. They share not just the same identity, or the same gendered aesthetics and habits, but the same problems, in the same place— not just looking alike, but living alike. Not just here, but here together. I’m very glad I got a picture of it, because it’s very hard to find good photos online.

I adore this painting, but in a jealous way. There apparently exist no artworks of people who resemble me inhabiting this same kind of comraderie with men, the kind of kinship which was the primary motivator for my own transition. This disclocation from history and community is the actual result of what we vaguely euphemize as “transmasculine invisibility.”

No matter how much I see myself conceptually reflected in them, my body, as a symbol, cannot be swapped-out in place of the ephebes without being reinterpreted as a typical heterosexual depiction of women’s objectification. I cannot place myself in a piece like The Ironworkers Noontime not only because I’m not an ironworker— my body and class have shielded me from a life where hard labor is just the inevitable cost of survival— but because slapping a pair of tits on any of these men would render him no-longer-a-man. Instead, he would be reinterpreted as a spectacle of women’s bold inclusion in the face of exclusivity and objectification.

I’m not really sure what to do with that, but my point is not to condemn the gallery for “failing” somehow to make my own personal internal conflicts the center of the stories they are trying to tell. They cover a remarkable amount of ground with more care than I ever anticipated. The whole purpose here at TAOG is to say that these feelings of displacement are not a condemnation of the culture, but a creative challenge— we are here to imagine new ways to express and symbolize that which has not already been done before, contextualizing the new alongside the stories of the old as time and technology continually change the world around us. That is what art is for, or at least, something art is especially good at.

So instead of complaints, this exhibition raises new questions for me: how could I possibly depict my affection for men without just asserting some recast version of fascist chauvinism or heterosexual obligation? How do I assert my own transsexualism as an expression of my freedom to be with men rather than my freedom from them, without cheap semiotic diversions from the body and life that I have? How do I create meaning, and communicate it visually, out of the hit-or-miss alignment I feel with queer men and women of both the past and present?

I mean, I don’t fucking know. I suppose I’ll have to do some paintings about it.

Thank you for sticking with me to the end. As a reward, have a pic of the most fun piece from the gallery:

I think part of why I like this show so much is that it didn’t market itself as either affirming or confrontational. You can tell a lot about a thing by how it advertises itself, I think. This show has been handled with a level of care that I really never expected to see, so really truly, if you get the chance to see it, go see it.

It might be your only chance to see some of these pieces which are on loan from the private collections of obsessive fans of particular artists— things like this one, which I also can’t find good pics of online. I wish I’d found the space to include it higher-up, for all its relevance to the unacknowledged experiential commonalities between women and queer men:

Worth noting that, by 1941, Nazis were so upset about Ernst Rohm and leftists calling them fags that they even started to execute/exile a handful of their own officers for homosexual offenses. A significant portion of those incarcerated for sodomy were accused of other crimes— mainly being Jewish or Romani, or some form of political nuisance to the Nazis— rarely targeting the German bourgeoisie, who seemed to generally believe they could just sort of keep their heads down and ride this one out.

Okay, the word the gallery used was ephebes, and yes, this exhibition includes paintings of children in a homoerotic context. This makes me deeply uncomfortable, but it’s a part of art history that is not going to go away just because I think it’s creepy— it would be weird to leave it out. I am not out here trying to sound like a gay libertarian arguing against age of consent laws, so let’s just mentally replace “ephebes” in our minds with “twinks,” because its an equivalent-enough concept for those of us who take it for granted that pederasty is bad.