what does it mean to be trans?

on US v Skrmetti, mutual aid, and the social construction of identity

I’ve been reading about the US v Skrmetti Supreme Court opinion and trying to write something about it in between packing to move to a new city. It’s difficult to explain the arguments from either the ACLU or the Supreme Court— their ideological lineages and selective dishonesties— without laying a mile of groundwork for those who are not already elbow-deep in arguments about what it means to be trans. Which is very frustrating and boring-to-read and not really contributing anything new to the conversation, you know?

More than that, I really dislike the pedantic, legalistic mindset that I get into when reading court documents, or the way it seems to skew my moral impulses. (I learned from my lawyer-dad that it’s fairly easy to make a convincing argument for something patently evil if you are in the game of manipulating legal precedent to that end— that was literally his job.) Besides, the language of law is so precise that it feels impossible to summarize without misrepresenting it somehow, so I won’t try. You can read the Supreme Court opinion & the ACLU’s legal documentation yourself, or you can get a brief summary from that handsome YouTube lawyer, if you like.

Instead I guess I’ll just be blunt and say that during my reading, I have been thinking of transmedicalists. I’ve written before about The Schism in trans culture, so I’ll just link to that summary in case that word means nothing to you. In short: Over the last decade and a half, I have watched as certain transsexuals took to Tumblr and YouTube to gripe about “fake” trans people, who seem to adopt a trans identity not because medical transition was something they wanted (let alone a medical necessity), but because “being trans” seems cool. A handful of those who have sought medical treatment for their debilitating gender dysphoria feel that everyone who trans’d their gender in some other way, or for some other reason, ought to be called out for stolen valor, because they do not fit the “real” definition of What It Means To Be Trans.

To be clear, I do not like transmedicalists, but I sympathize with their anxieties and I feel a duty of solidarity with them as fellow trans people. We love to use the metaphor of “the trans umbrella” to describe the vast diversity among people-whomst-identify-as-trans, but we rarely acknowledge that one only shares their umbrella when it is raining, and the forecast is not looking sunny for any of us right now.

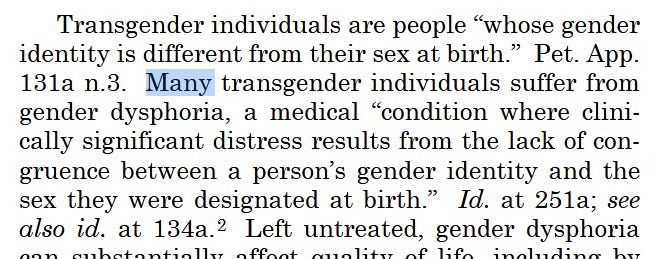

Anyway. Transmedicalist reactionaries feared that the popular definition of trans identity—i.e. a transgender person is someone who identifies as a gender other than the one they were assigned at birth, rather than someone who feels clinical distress about their gender— would have consequences for the latter’s access to healthcare. They were soundly rejected by both trans culture at large and just about every institution that deals with trans people,1 and the Skrmetti opinion seems to have proven them right.

The ACLU and their allies did a little lie in their court case, repeatedly claiming that “clinically significant distress” is a definitional feature of a gender dysphoria diagnosis. I’m not a lawyer so I don’t know how to look up whatever that 251a citation is, but that is just not true— at least, not if you care at all what the DSM has to say about it. Even in a medical setting, you don’t have to be suicidal to be trans— you just have to want it badly enough.

Unlike the transmedicalists, I like that, and I would like it to stay that way. I strongly agree with Andrea Long Chu’s proposal that transition ought to be understood as a matter of agency & desire rather than a cure for dysphoria (or at least, that wanting, needing, and being are not so easily teased-apart). I appreciate the efforts of medical institutions to create a justifying framework by which they might provide for as many people as possible, and still convince insurance companies to cover the expense. I like it very much that the culture has successfully constructed trans identity as something open-concept, with doors unlocked and open.

What upsets me is the way that, over the last 30 years, trans culture at large has seemingly demonstrated to dysphoric transsexuals— people like the plaintiffs in the Skrmetti case, stressed-out children who will suffer in the extreme if their healthcare is taken away— that our own personal validation is too great of a sacrifice if that is what is required to protect them under the law. We the people have decided that “the definition of trans” must be something that is, to put it mildly, politically inconvenient for the most desperate among us. We largely have done so by mocking, insulting, arguing with, and ostracizing-from-our-communities some of the exact people who most badly need to be protected, mostly because they were rude to us first. We have frequently accused them of a power they do not actually possess— the ability to meaningfully “gatekeep” anyone else’s internal sense of identity.

We did not reject transmedicalists because their fears were unfounded, but because they made other kinds of trans people feel excluded.2 Put differently: we did not reject them because medical transition has never been a genuine survival-necessity for anyone, but because they violated the principle of self-determination which has come to be the singular defining feature of trans identity. Their biggest mistake was believing that they had any capacity to police the boundaries of an identity which is heavily socially-constructed, whose meaning is inevitably determined by collective consensus.

I am not here to pretend I know how civil rights lawyers ought to do their jobs, nor am I going to castigate the trans masses for deciding that the only legitimizing obligation for adopting a trans identity is deciding that you are one of us. But I think we have to acknowledge that there is a significant gap between shouting “protect trans kids” at news cameras and doing what must be done to ensure that they are protected, even if it requires some level of personal sacrifice. If we are not willing to re-define trans identity into something that the ACLU can work with, what are we willing to do? Most importantly, how do we take care of one another if we are all broke, stressed-out, and know that the Supreme Court is likely to shoot down any argument in our favor for what could be the rest of our natural lives?

CIRCLING THE WAGONS

My fear right now is that trans culture will respond to anti-trans lawmaking by clenching down on who we allow to participate in trans community— our social scenes, our support groups, the interpersonal scaffolding which should serve as a network-of-care in times of terror and scarcity. I think of Hunter Schafer, in 2022, who responded to the early Florida laws restricting trans minors’ healthcare by taking to social media to kvetch about nonbinary people. This sort of bickering is nothing new, and it’s far more painful to soak up this kind of misplaced frustration face-to-face than to read about some celebrity opinion on the news.

I also worry that, in focusing so heavily on (in)validation— as if it is the height of both trans suffering and trans mutual aid— we have grown indolent and weak-willed in the face of serious adversity. For instance, I am not impressed with Assigned Media, an independent trans journalism org, going off about “who gets to define you” when the issue at hand is who gets to transition. While doctors and judges have no magic powers with which they can spiritually incribe what kind of person you really are, they have significant power to control how smoothly we move through the institutions that we are forced to interface with in order to get what we need. We (and I do implicate myself, here, too) are very much in the habit of conflating opinions which make us feel bad with the limiting, damaging, deterministic policies that lie downstream.

If shit is really going as badly as we all say it is, our support for each other must amount to more than thoughts and prayers and “babe you are, like, sooooo valid” social media posts. When institutions fail us, we must create our own; if we cannot convince the powers-that-be to provide for us, our only choice is to sidestep their approval process to cut new pathways for getting what we need and want. We must buy and build housing, provide transit and services, do whatever we can to care for those who are in need. We must remain locally connected so that whisper networks and secret infrastructure can maintain itself without a digital paper trail. This is the example set for us by feminist activism in the face of abortion restrictions, and I think we would do well to follow their lead.

That is not to say that our words and our cultural norms are useless in this endeavor. Thus far, the hyper-individualistic version of trans identity we currently have has failed to motivate us to face any serious risk in doing the labor of mutual care. The vast majority of trans people I have met approach trans identity— and thus, participation in trans community— as a question of “what will it do for me?” to the exclusion of asking “what do I have to offer?” As Simone Weil would put it, we want rights without obligations— we want to be taken care of, but when taking care of others is difficult, we flinch. When it comes to defending the nebulous reality of an inner life, we are all primarily oriented inwards, towards the self, more than towards each other. The result is a culture where trans identity has been heavily commodified, where we readily tear each other to pieces if someone impinges on our entitled sense of ownership or our demands to be delicately catered-to. But we do not have to operate this way.

I don’t really have any ability to affect The Law. I do not have the apparent authority of an academic, a lawyer, a doctor, or an influencer. I have very little money to give, and I am not ~strong~ in mind or body. I have repeatedly lamented that I have little to offer, and what I do have to offer— open-hearted company and a shoulder to cry on, a firm hand to hold while doing what is difficult and frightening, maybe some pretty pictures and the knowledge of how to make them yourself— is not worth much to anyone. Still, I would like to try and offer a little clarity on how we think of trans identity, a way-of-understanding that is perhaps more concrete and motivating than merely We Who Identify As— not as a means of trying to enforce agreement, but to observe & interpret in a way that bolsters our need for meaning and solidarity in difficult times.

DEFINING TRANS

I think the only reasonable way to understand “what trans identity means” is to look at the people who identify as trans and see what we have in common. The argument of the Supreme Court is that, because trans people have no “obvious, immutable, or distinguishing” characteristics, we cannot be considered a coherent identity group that could feasibly be discriminated-against or protected. To be sure, “identifying as” is seemingly the only consistent feature that holds true across the great diversity of trans people. Since dysphoria and medical transition are not universal among us, it implies no commonalities of feeling or experience; it requires no qualifications the way an identity like doctor or teacher do; it carries no relational meaning the way family-identities do, like brother or mother or cousin.

I understand why some people find this solipsistic and recursive. Something something blue-hair-and-pronouns, I identify as an attack helicopter, etc. Still, this definition is very intentional. Here we also run into the limits of postmodern deconstruction: by deconstructing gender, questioning how it is defined, we still inevitably make responsive choices about what we intend to do with its constituent parts. By examining further what trans people do— not merely how we feel or describe ourselves— I think we can sniff out more of these shared values which make up the substance of trans identity.

Since we have different experiences, different aspirations, different political or metaphysical explanations of gender’s structure, etc, we are held together by certain collectively-determined values. By grounding our sense of identity in an internal feeling, we have prioritized individual agency as the primary mode of participation: I think I am trans, therefore I am trans. We reject the way that gender is so often an identity both ascribed and conditional— you are X whether you like it or not, but in order to be a “real” X, you must do XYZ. In response, we do our best to expect nothing—demand nothing—from those who want to participate with us. We are trying to be serious about the principle of democratic pluralism— whatever your gender means to you, you are welcome with us. When we transition in the face of great risk, we reject wealth, status, public approval, comfortability and even safety as worthy goals to steer our lives by.

What this tells me is that, all else being variable, we are trying to act on certain beliefs: that every person— including the strange, the contrarian, the unproductive, and the needful— possesses an equal and ineffable dignity, and their presence is intrinsically valuable. That trying to enforce dominance hierarchies— including hierarchies of meaning— is an evil temptation which must be resisted tooth and nail.

But, ~as I am always saying~, it is not enough to define ourselves by what we are not. If we want our identity to have meat on its bones— to dignify our inner lives by allowing them to touch the world outside our skulls— it would help to act on these principles in the positive more often. We could choose to treat identity as an active process of creating rather than passively existing.

KEEPING THE FAITH

I find it very interesting that, in arguing both for and against trans rights, the Justices of the Supreme Court make comparisons between transness and religion. They correctly point out that transness is not “immediately ascertainable at the moment of birth” the way that race, sex, or nation-of-origin are— but neither is religion, an identity we protect in our law even though it is changeable and chosen.

In this light, transsexuals are sort of the monastic order of trans culture, as funny as it sounds to phrase it that way. I doubt it would hold up in court, but I really like this framing— least of all because I don’t think that committing to an ~irreversible~ medical transition is any more bizarre or unhinged than becoming a nun. We can give honor to those who have gone to great lengths to embody this central Trans Principle of self-determination-at-all-costs, without treating extreme commitment as a requirement-for-participation. Of course, not every Christian wants to take vows of poverty and celibacy, but they give appropriate respect to those who do— while understanding at the same time that you are not going to hell just because you don’t join a convent.

Perhaps a less-absurd comparison is to the social construction of butch & femme identities— butches accepted the risk of being visibly queer and provided protection within their communities, while femmes could fly under the radar in order to find work and bring financial support back home to their loved ones. Whether daring or pragmatic, the ways they embodied and acted-out their identities were generative in different ways, creating a social world greater than the sum of its parts. Whether adopting these identities felt chosen or inevitable to any of their members, their meaning was grounded in commitment to mutual provisions-of-care; their aesthetics symbolized both personal authenticity and consequential, interconnected ways-of-living.

I have an inkling that, if transness is “trendy” right now, it’s because people are thirsty for a form of meaning-making which operates this way. We have watched Christianity— where most of western culture has gone looking for explanations of gender’s meaning and substance— mutate into something cruel and controlling under the influence of talk radio and megachurch profiteers. We have also found that liberal consumer culture, with its focus on displays of wealth and trend-following, is empty and unsatisfying, somehow both rootless and hierarchical at the same time. Gender, then— and exerting our agency over it through declaring a trans identity— becomes a tool for trying to make meaning in the ways that these dominant forms of culture have failed us.

All of this in mind, I think it would be worth our time to think of trans identity not in terms of how we feel or what we want, but how we might fulfill our obligation to support the right of others to self-determine. We can think of self-determination as not only what we want to receive, but what we may voluntarily give when we see that the rights of others are not being properly upheld, even when giving is difficult. Instead of understanding inclusion as an expresson of pity for people the mainstream is hostile or indifferent to, we could understand that diversity is genuinely enriching because everyone has something to contribute— even people who are very different to us or are sometimes hard to get along with. Trans identity may not be literally “spiritual” in the way of a religion, but it can be a means for organizing ourselves in the spirit of our principles, and for motivating the difficult labor required to live by them.

Elevated Access is a nonprofit that provides private flights to people who must go out-of-state to access gender-affirming healthcare and abortions. Here is a link to their donations page.

If you are interested in medically transitioning, the Gender-Affirming Letter Access Project can put you in contact with a therapist who will write you a surgical letter as cheaply and effortlessly as possible. Erin’s Informed Consent Map can help you find a local provider who will likewise make the process relatively painless. If HRT is illegal or just too difficult where you’re at, diyhrt.wiki has information on how to start hormones as safely as you can without the oversight of a doctor.

For dessert: check out my friend Taylor’s recent advice about organizing third spaces through her decade of experience volunteering at a community garden, or this very nice Sam Bodrojan piece about why SOPHIE is still the future.

Note that the prior definition is effectively universal in institutions that have any reason to explain what a trans person is. It’s the one held by the Human Rights Campaign, Harvard Med, the ACLU and every state-appointed lawyer that wrote in to support their case, to name a few examples.

I mean, we tried to pretend their fears were unfounded. Ten years ago, it was not unreasonable to say, “simmer down, doctors are not paying attention to teenagers on tumblr making up new genders.” But the philosophical deconstruction of the medical model of transsexualism did not begin in 2013, and the world is a very different place now.

Okay I’m stuck on the supreme court’s argument that trans people have no “obvious immutable or distinguishing characteristics” and therefore cannot be discriminated against or protected. because, when if you tried to get into it, neither do women as a category? Or men for that matter? Like gendering anyone is a snap judgement at the end of the day, its a vibe and not able to be described so precisely. On that basis I feel like being gender nonconforming is more than enough to constitute an obvious and distinguishable characteristic. Idk if this makes sense lmkkk

In the metaphor of the monastic commitment, I feel like you bring an Aquinas-like vibe to the table, the effort to reconcile and explain and work through the logic in a readable way feels resonant