I have to tell you something: There is something wrong with me.

In case you don’t know me very well, I eat like a child. I am over 30, and my diet is all cheetos and chicken nuggets. If you make me bite into a burger or a lasagna or a salmon roll, I will start trembling and sweating and probably throw up. I’m sorry, but I cannot put up much of a conscious fight with my amygdala, here— it seems that whatever part of my brain is supposed to register that food is food just doesn’t function, maybe warped by some trauma that happened so early in life that I have no memory of it. I am also hyper-aware of my body, both alone and in public— the way my chest bounces when I walk, the way my shirt drapes over my nipples, whether my body language adequately conveys I promise I don’t bite and please leave me the fuck alone and balances them appropriately. Due to some combination of failures in cognition and character, I am frequently incapable of talking on the phone or going to the doctor or working a day job without a disproportionate measure of misery. I pace, I stim, I stutter. I smile like an anxious dog. I either love things or hate them, I obsess and I avoid with equal fervor. I write about art and gender not as a vocation or a craft, but as a compulsion, an all-eclipsing need to dump what is inside my scrambled skull into a secondary container which can then be shared, examined, and thereby grounded. Here, couched in a respectable font, I shake my brain into a jar and then show it to you and ask: Is this real? Am I insane??

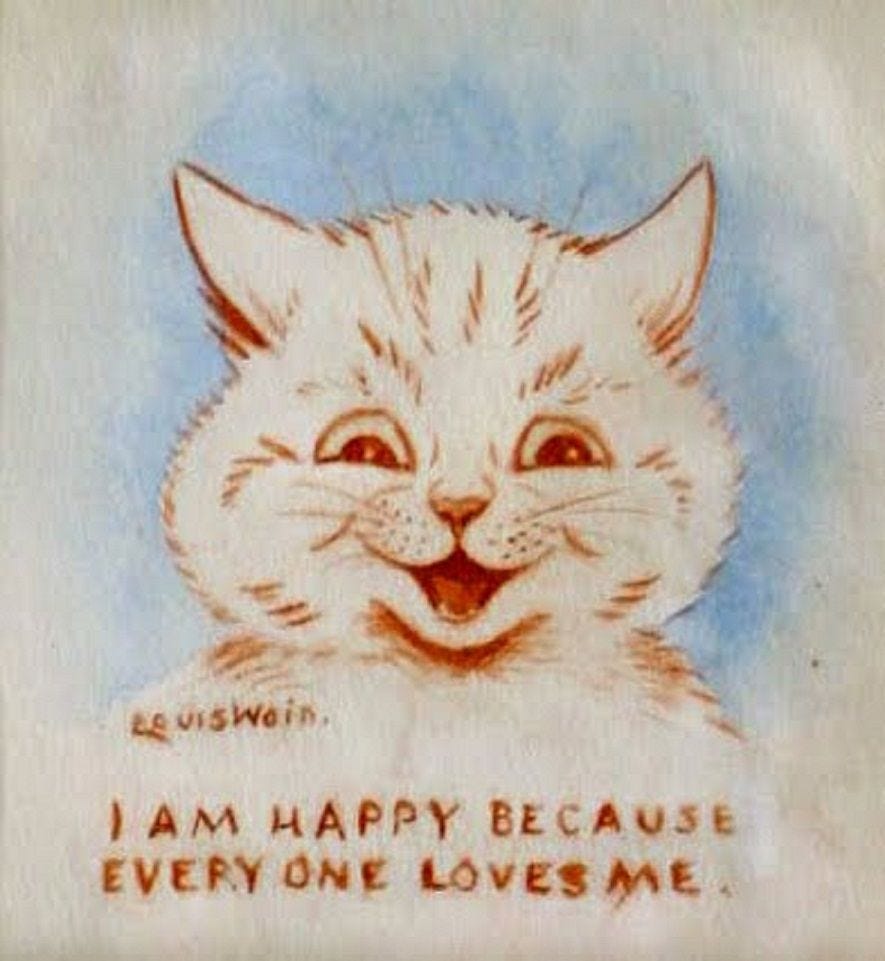

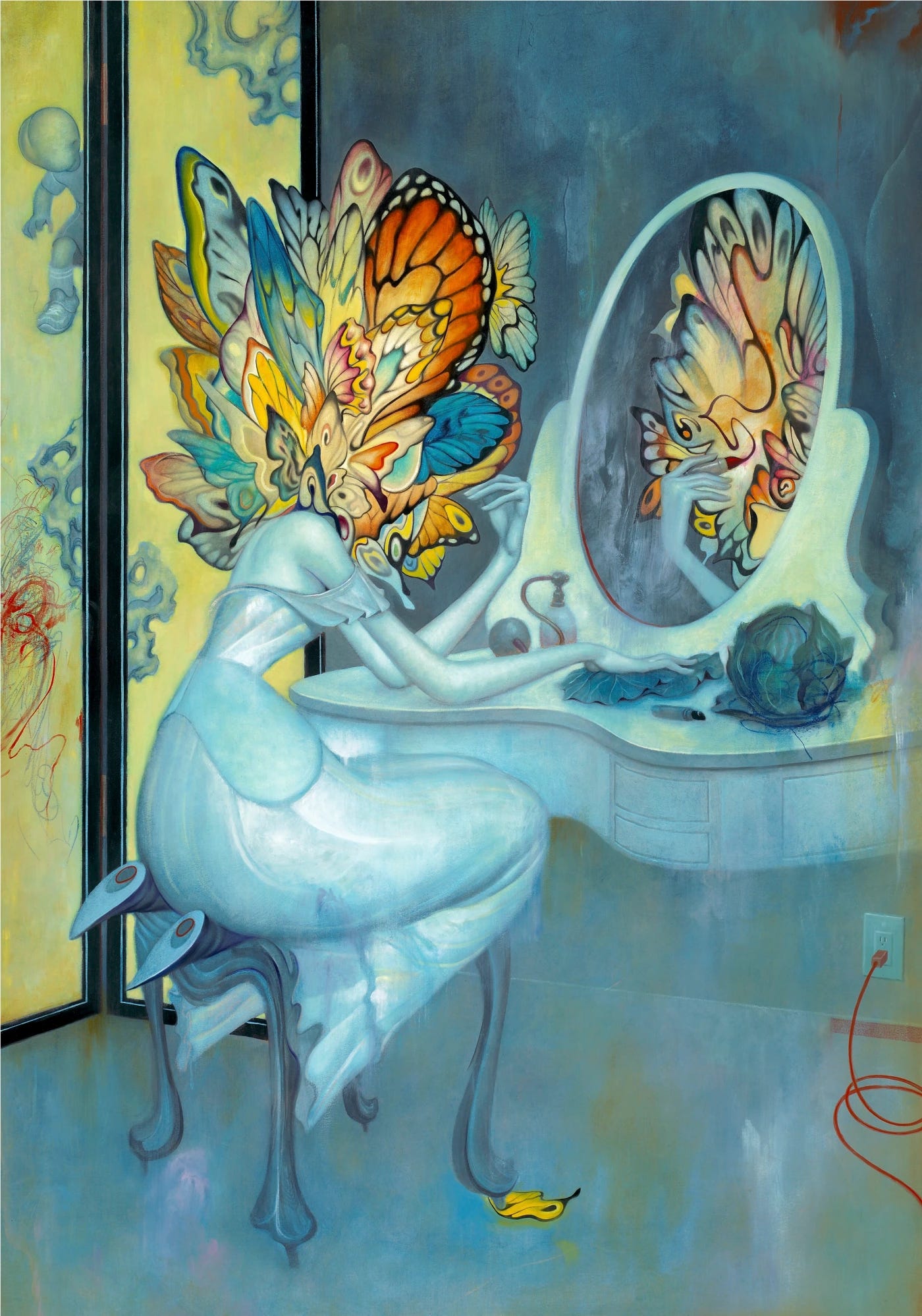

We call my interiority things like gender dysphoria, attention deficit, anorexia nervosa, post-traumatic stress, autism, bipolar, borderline personality, this mess of euphemisms for butterflies that flap all around the place and are arduous to pin down. The go-to treatment for [butterflies] is some combination of psychiatric medication and Dialectical Behavioral Therapy, a pragmatic little toolbox of cognitive techniques for developing emotional resilience and stabilizing your social interactions. In spite of behavioral therapy’s crisp problem→solution structure, sticky things like personality disorders and bipolar are not generally cured, only coped-with. Borderline is sometimes referred to as “the modern hysteria,” since its diagnosis hinges on subjectively assessing “extreme” emotions (also: it is applied to far more women than men, at a rate of 3:1).

I think if we’re using vague words like “dysphoria” in our technical language anyway, then at least calling my bullshit “hysteria” is a little more evocative. It implies that not only do I feel bad inside, but I act in a way that is socially unacceptable and, like, maybe it’s all a malingering put-on, you know, like, who can say what’s really going on inside my head? Obviously you can’t— you aren’t stuck in here with me— but neither can I, and not for lack of trying.

Hopefully I don’t have to tell you this, but being a hysteric is humiliating. My shit is not even that wild, as far as madnesses go— I don’t hallucinate, I don’t break things or scream at people, I haven’t gone and got myself evicted or arrested or drank a bottle of mouthwash just for the alcohol— but I still cannot clear the high bar of sanity required to move through the world without friction. If the only thing you eat at most restaurants is french fries, you can’t get dinner with anyone— dates and colleagues will expect an explanation, try to be polite, and still decide you’re a fundamentally unserious person; the family will try to feed you and be offended-disappointed when you won’t even put their hard work in your mouth. Doctors’ offices lose patience (ha) if you miss too many appointments or can’t navigate an automated phone directory, and “I can’t cope with the confusing layout of the waiting room or its loud fluorescent lights,” or “I’m afraid I will say the wrong thing to the robot, and then I will have to start over again,” does not earn much understanding or assistance. You have to walk this tightrope of expressing that you really truly do need to be accommodated, but also you are not so insane that you should be locked away from the wages or medicine or people you need to get by.

Society will somewhat tolerate hysteria in some extreme circumstances, like grief, but to be hysterical as your default state is to be an eternal problem child. It consigns you to a life of hearing it’s not that serious and oh, relax and watching the light fade from others’ eyes as they approach exhaustion under the onslaught of your emotion. You vibrate at an overwhelming frequency, and the organ quickly grows numb to it. It is nearly impossible to advocate for yourself as a reasonable person, deserving of agency when you consistently come off like one giant raw nerve.

It takes exceptional self-scrutiny to recognize which feelings ought to be reigned in a bit, and which reasons for doing so are legitimate vs repressive.1 I consider therapy, at the societal scale, to be the means by which we train unruly hysterics to behave themselves in a society which has little patience for them, and that goal offends my sensibilities. Society needs hysterics— mystics and psychos and perverts, those who antagonize our complacency and poke at the parts of us which have gone all static-numb. And of course we all need outlets for our own repressed hysteria. “It is no measure of health to be well-adjusted to a profoundly sick society” and all that, you know.

But, I say, perhaps through gritted teeth, I still think of my time in DBT as essential to my emotional survival and also my maturation into a less-chaotic-and-destructive person. Therapy was good for me and I enjoyed it, at least when I could afford a therapist who could afford to give a shit. I needed to wrestle with my damaged ego, develop both coping tools and discipline around my behavior, even in the presence of overwhelming emotion. Fortunately, I happen to be the sort of person who gets along pretty well with therapy. And, lucky man that I am, society contains plenty of people who will never stop telling me that going to therapy to fix myself was the objectively correct thing to do.

This is the contradiction which faces everyone, with varying levels of friction: be yourself, but behave. When our culture frames men and women through a dynamic of predator vs prey, negotiating this contradiction means shouldering the weight of society’s heavily-gendered moral sensibilities. What I mean is that, throughout much of American history, female hysterics have been at the mercy of the men who control their livelihoods, and so we narratively frame feminine hysteria as either a minor annoyance or a helpless wail from one who pleads for rightful agency over her own life and mind. When we think of male hysteria, we of course characterize it through the lens of the predator: hysterical women might make some shrill noises or walk into the sea, but hysterical men will fucking kill you.

Society is enticed by the idea of a femme fatale because it is endlessly novel for a woman to enter the role of the predator, and we sympathize with her violence as the underdog, revolutionary kind. But, we progressives say, the narrative of a male predator is not enticing or sympathetic— it’s vulgar, in the sense that it is both common and repellant. We have seen this story many times before, and we still do not much like that guy. We resist the urge to treat broken women as worthy of scorn, but we inevitably frame male hysteria in terms of the danger he might pose to everyone besides himself; when the harm is turned inwards, we consider first what and who he must be neglecting with his malaise. Part of the ennui of men trying to write about man-feelings is that it is terrifying to make and share art about the fear of your own capacity for evil, and it is humiliating to face your fear and ~speak your truth~ and realize that no one cares. It’s boring. Your witnesses aren’t shocked— they’re not even listening.

In terms of fiction writing, we view taking power as an active choice while relinquishing it is a kind of passive inaction. The social justice narrative aimed at men frames power in exactly the opposite way: we describe [white/straight/cis/etc] men as victims of endemic patriarchal brainwashing such that exerting power is their passive state. We frame relinquishing power as an active and effortful choice which entails Doing The Work of interrogating your ego and your presumptions about the world, changing your language and humor and how you relate to others. I think this reframing is ingenious and effective at expressing its point, but still, we do not have a lot of stories (or commentary) that might narrativize this “active” “dismantling” of masculine dominance as something more complex or enriching than doing our homework.

Critics say the audience craves variety, but masculine subversion of the expected— depictions of men as vulnerable prey animals— are rarely so empowering or exciting as, say, rape revenge films or the final girls in horror movies. I think of the excruciating opening scenes of The Passenger (2023), where the protagonist is forced to eat a moldy burger by his bullying coworkers. Or the scene in Under The Skin where Scarlett Johanssen can’t tell that the man she’s trying to go all praying-mantis on has a facial deformity.2 I find both of these scenes viscerally upsetting to watch, so I get why society at large isn’t eager to empathize with genuinely weak, humiliated men. “Emasculation” may accurately describe a man debased by displacement from manhood, but I think these examples are better described as a masculine kind of emotional torture. The pain comes not just from being vaguely mistreated or hurt, but from the specific ways that men engage differently with men vs women, or their experience of dropping the ball on some version of masculine expectation.

Films of men-as-prey are rare compared to vigilante/vengeance flicks like Death Wish or Falling Down or Joker— we can stomach them only with the promise of redemption, through either camaraderie with other “outsiders” or an eventual explosion into violence. In the absence of community, the other narrative that offers catharsis and meaning for loser men is to fulfill your telos and become a predator, no matter the cost to your soul. What else is left within the realm of possibility when both of those options are impossible? I don’t know, but if you don’t either, then maybe you are not up to the task of even fully outlining this void, let alone filling it.

Being a man— and reading how men are described and advised by the progressive literati— often feels like being insane. You are presumed to be living in a totally different reality, but your perspective on that reality is not to be trusted, let alone respected. You are either a monster or an object of pity, and even divulging your real honest truth risks suspicion of manipulation and malingering. Everyone ruminating on “vulnerable male fiction” on substack and beyond lately seems so insistent about welding men’s pain to the specter of misogynist violence, as if that’s all we could possibly have going on under the hood, and now I’m the one who’s bored and annoyed. Our culture has spent no little effort stoking and rationalizing paranoia about male violence (what better to sell ring cameras to all the suburban true crime podcast girlies?), and so trying to do “vulnerable” writing for/about men is just the Zootopia problem all over again: no one pities someone who is reasonably suspected of being a predator. But I am not here to watch children’s movies, and when “male vulnerability” is conflated with “misogyny,” or when “violent media” is conflated with “shallow shlock,” I feel like I am being talked down to.3

What we should take away is that viewing gender through the dynamic of predator vs prey has always been reductive, in fiction or in life, but that allegory is still hanging around in the culture like stale weed smoke and maybe somebody ought to write something that looks that problem in the eye. We should recognize that if men are paying attention— and clearly some of us are— the moral heft of implicit [emotional-physical-sexual-economic] violence towards women weighs heavily on everything that men do or make, and not only the white or straight or cis ones, either, nor only us pathetic hysterics. Maybe then we might get some books from people who have something actually interesting to say about the modern masculine condition.

Forget violence for a minute— What about men who are not pursuing a dominant style of living, but still want to be men rather than retreating from manhood altogether? Can anyone write a man who hasn’t the interest or capacity for violence, but still has to navigate life treated like a bull in a china shop anyway? How does a man express the depth of his admiration and gratitude to a woman who might just decide that he’s trying to hit on her with airs? How do you trust anyone or ground yourself when everyone says they’re afraid to tell you no? How heavy are the sins that fall short of misogyny and murder, and how do you carry on and repent when you know that no personal penance will ever be enough for what you or your forebears hath wrought? What if, instead of projecting self-hatred outward onto others—those we meet in the gutter, in bar back-alleys, in seedy motel rooms and seedier message boards— we cultivate genuine affection for our fellow fuck-ups, and thereby learn to love ourselves through our resemblance to them?

The Passenger (again, the one from 2023, not the one you’re thinking of) is pretty corny at some points, but it’s a rare depiction of a boy who not only rejects violence, but is fully traumatized by his own capacity to hurt others, even by accident. He is kidnapped by a man who pities him, and expresses that pity by forcing him at gunpoint to face his past and become a more self-actualized man. The gunman thinks this will be a journey of repentance and growth, but we find the boy forced to challenge the timidity and numbness that enveloped him in the wake of his community leaving him to the wolves. This is a depiction of masculinity that speaks to me: a man who has been made small by the conviction that others deserve care that he himself does not. A man who cannot imagine himself as anything anyone would ever want and, in the absence of ideas for what penance he could do or what better he could be, can only try to disappear. An antagonist who thinks they know what’s good for him, only to realize they don’t really know him at all.

A lot of the literary meta-commentary from would-be authors flies over my head, but I’m trying here to dialogue with, among other things, a couple of other substack essays I shared recently in notes. You might have missed if you (wisely) do not treat substack like it’s twitter. This one I liked for its empathy for men’s struggle to meet the high bar of feminist standards for good behavior, but also disliked for its conflation of all ~dark masculine feelings~ with incel-style heteropessimistic misogyny (both features it borrowed from the inciting essay which asks that the public be patient and tolerant of sticky masc feelings that aren’t particularly PC). This other one I generally disliked, but I think it’s worth reading as one of many examples of how progressive commentators discuss “men” as if they mean all of us, but really are only talking about the tiny subset which contains the most insufferable men they can think of— and how men distance ourselves from maleness rather than try to wrestle it back from the men we don’t want to be. Critical though I am, many thanks to both of these writers for their works which have helped me triangulate my own thoughts, and for responding so graciously when I critiqued them “in public.” A real Dudes Rock moment for us all.

To anyone who wants to speak on the ennui of the masculine condition: lots of you don’t listen to anything even resembling punk music, and it shows. Give it a try sometime. As it turns out, when you aren’t worried about impressing a publisher, you can really just make whatever you want.

The ubiquity of this struggle makes us all hysterics, but I can’t judge that much. I don’t know that I will ever really develop this discernment in full— I definitely can’t do it by myself, but finding helpers who are wise, willing, and engaged is like pulling teeth.

Did you realize he was trying to suss whether she was flirting with him just to be cruel? Did you cry when he waded into the void and was shelled like all the rest?

I am not taking time here to dig into the actual depth and worth of stories about men who communicate primarily through the language of violence because I have been begging my boyfriend to do it for me and contribute an essay about Ichi The Killer and Shigurui: Death Frenzy. He has the best opinions about what is compelling and relevant about men’s action stories, and he can explore this way better than I ever could. If you would like to read that, please tell him so in the comments.

I would love to read about your boyfriend's opinions. This was also a really compelling piece :D

This was so good.