on going to content school

if you scream in the prairie, it doesn't even echo

This entry includes images that are NSFW.

A little while ago I was interviewed by The Culture We Deserve podcast for an episode about art school— what is it for, what does it do, what does it mean for us that art schools are downsizing (or, in PAFA’s case, ending their degree programs entirely). I go out of my way to avoid thinking about art school because it was a deeply immiserating experience for me, but unfortunately my favorite contemporary essayist is writing about it a lot lately, which means my brain is cooking.

If we’re being technical, I graduated in 2016 with a BFA in Illustration from the Kansas City Art Institute and have since built up a “successful” “freelance” “career” making digital paintings for random internet people, including a handful of generous patrons who buy new work from me on the regular. If we’re being honest: I don’t think I have ever learned how to make art, which is why I don’t.

When I got to college at 19, I was jealous for Experience. I didn’t really know anything about how the world worked or about what art is, and I knew it— but I did know how to draw. I was an Idiot Expert, wildly emotionally unstable and desperately undersocialized, heavily sheltered from 90% of pop culture apart from a handful of cartoons and videogames and anime (back when those things were still just for nerds). But I knew the Reilly method by heart, had already put in a good chunk of my ten thousand hours studying Eisner and Bridgeman and Gurney and Leyendecker, and (I would soon find out) knew photoshop more intimately than any of my professors.

I had no inkling of what “building a career” might look like in practice, but I fantasized about one day becoming an art director for Pixar or Elastic, painting character concepts for videogames, pouring months or years of work into graphic novels. I wanted to make everything and make it well. I hoped that if I went to school, I would go from good to great, and then the meritocracy might reward me with an adult life of meaningful labor and maybe even collaboration with artists I admired. But all I really knew was:

I was good enough at drawing and painting that maybe, with enough education and luck, I really did stand a chance at getting one of the few jobs that pay you a decent living to do that.

I wanted to study and get better at art, even if it never materialized into a prestigious or well-paying job. I would make peace with slinging groceries just to make rent so long as I could also make my little comics or paintings or whatever to the best of my ability.

If I didn’t get the fuck out of Kansas suburbia, I would probably kill myself within a year.

CRAFT

I expected art school to be like a real-life version of conceptart.org (rip), a place full of other artists whose skill and dedication matched that of my internet peers. Once I got there, I found out quickly that my ability to draw and paint was more like a party trick that no one else was interested in learning. (I also learned the hard way that just because people are impressed with your skill doesn’t mean they want you to share what you know or teach them anything, even if you are ostensibly both “there to learn.”) The method taught to illustrators at my school had little to do with classical methods of study and mostly drilled down to think less, draw more.

The idea is that if you go to enough places and fill enough sketchbooks, then— by law of large numbers— some of it will eventually be good art, whatever that might be. Mastery of any medium requires a lot of study and practice, and most people find those things deathly boring, so “daily challenges” have always been chic. When you are a new artist trying to build up good working habits and muscle-memory, having a little challenge for yourself is supposed to help you count your progress and slog through a large-scale project one bite at a time. Take a selfie every day for a year! String them into a time lapse and watch your hair grow in fast-forward. Now do a hundred 6”x6” paintings from life, one every day. Draw a slice-of-life comic every day— no wait, a comic every hour, then remember to do it again next year.

Events like Inktober have evolved away from being a motivation tool for practicing a specific and notoriously-difficult medium and towards being a brand’s hashtaggable event inspiring you to just make stuff, but make a lot of it, ideally while everyone else is also doing the same thing. Here is your 10th monthly challenge that will encourage you to crank shit out at a breakneck pace because thinking about what you make wastes valuable time you could spend being productive. I learned slowly that being an illustration major was not about building your technical skills or expressing anything in particular, it’s about throwing shit at the wall until something sticks, usually on a tight deadline. Now that the Content Creator™ gig economy has had another decade of refinement, it’s ever more apparent that this was training us into a creative practice that now amounts to a constant stream of posts for the posts god.

And unfortunately for me, hustle is my kryptonite. I don’t find studies boring, but urgency, competition, and performance are absolute poison to me. I avoided entering art contests like the Society Illustrators (a KCAI favorite) because I knew already that I was both a sore loser and a sore winner, assuming I could bring myself to produce anything at all if I was aware that this painting was born to be judged. Doing anything every day feels Sisyphean and the idea of winding up with a mountain of work at the end of a short period of time does not make me excited— it makes me want to lay in the middle of the floor and moan impotently until I start decomposing into the rug. Artists who talk about their daily routine of sketchbook life-drawing over their morning coffee strike me with the same malaise as watching an influencer talk about their skincare routine. That sounds exhausting.

In this environment, it felt like my desire to think about what I was making and looking at was not only not supported, but not possible. I had to crank out 3-4 paintings a week for my studio majors, plus additional projects for elective classes, plus lectures+notes+papers+tests for art history. I was also supposed to do my retail job every day that I wasn’t at school, go to therapy once a week, and figure out how to go outside and feel things and be a person in the world for the first time. Thinking would cost time and focus and I did not have any left.

For all of our heuristics and habits and marathon-runner dedication, it remains that simply making a lot of paintings gives no guarantee that any of them will be worth a damn thing, artistically or financially. What I learned was that in order to be good at art, you have to make a lot of it, and most of it will be bad. If you can’t stand knowingly making bad art, then you’ll never make any art at all.

CONCEPT

On the conceptual side, the goal of constant production via sketchbook is to shake out your brain onto the page like a box of legos and hope that once a lot of disparate idea-pieces are visible, you can connect and refine them into something clever. As designers and engineers have attempted to become more like artists, it seems artists have also attempted to become more like machines, but the product we produce is our own Freudian id. The problem with methods like brain dumping or Lynchian surrealism is that they do not necessarily lead the average person to anything interesting— the people who are good at those things already had something unique going on between their ears. The elephant in the studio that nobody around me seemed to notice was that quite a few of the illustrators who were prolific at barfing their id onto the page were creating works that were vapid, repetitive, and intellectually bankrupt.

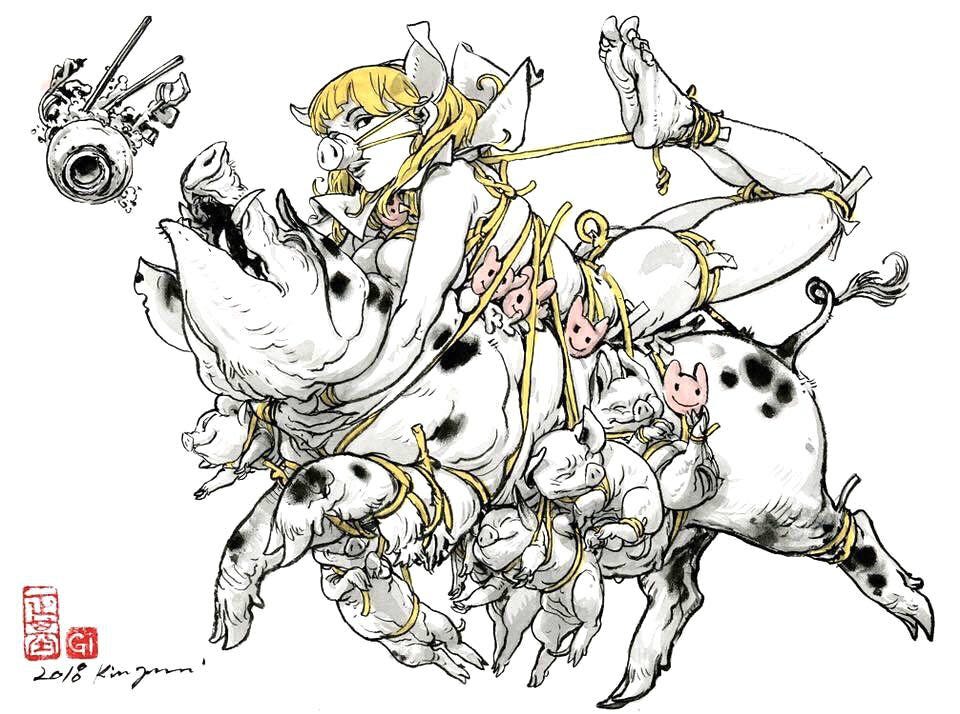

At a certain point, I had an emperor’s-new-clothes moment with the work of Kim Jung Gi. When I said earlier that technical skill wasn’t worth much to my classmates, that was a lie—everyone I knew who cared about drawing idolized him, because watching him draw was truly incredible. Videos of his impressive wall-drawing went viral over and over on the early internet. Gi, like a thousand other illustrators of his era, also clearly drew inspiration from his own spank bank, but has never been seriously described as a pornographer. When I pointed out to multiple people that a professional portfolio full of panty shots and titty nonsense did not inspire in me a lot of respect for a person’s art, the refrain was the same: but look at how well it’s drawn— besides, this is just what I like drawing. We were too cowardly to ask what did he mean by that? about a guy whose ~pure creative intuition~ frequently combined imagery of naked women with squealing pigs.

And it wasn’t just men, either— as it turns out, the id of your average millennial woman is not actually that far adrift from that of Charles Dana Gibson. The vast majority of my classmates were women, and while I was a baby feminist watching Anita Sarkeesian talk about the male gaze, many of my female classmates filled their sketchbooks with pinups. They sometimes inched the goalposts away by making their figures tanned and curvaceous, as if a skinny white woman making art of fat black women was necessarily less objectifying because, I don’t know, something something ~the sisterhood~ etc. When given an assignment to make a list of 100 things we liked to draw or themes we liked to incorporate into our art, every member of the class included “boobs” somewhere on their list.

But whatever, right?— We were all 21 and stupid, maybe I’m being a little precious about the nude female as the default objet d’art. It’s legal to be a pervert, it’s the lack of honesty about what this is that gets to me— it’s not porn, it’s not sexist, there’s nothing to think about here, don’t take it so seriously. I’ve drawn a lot of sexualized men, after all, both to shock and entice the viewer, but the difference is one of context and integrity. Tom of Finland’s eroticism is never denied, and I own my status as a smut peddler.

What frustrates me about this idea of creativity as a pure and beautiful expression of the self, no matter what it looks like, is that our selves and our feelings about beauty are informed by the culture around us, which can take hold of our hearts and run away with them if we let it. Today, when I see queer artists begging for “cozy” art, I am rocketed back to the living room of my christofascist parents with their giant, ornately-framed Thomas Kincaid print. Encouraging us against locating our own taste in the context of our influences is the opposite of what I needed from art school. No one is an island, and nothing is ever “just pretty.”

EXPERIENCE

I think part of why I like Jessa’s writing so much is that we are both from Kansas. Her writing speaks to my experience of growing up in a place that leads many small-towners to the same realization: if you want to feed your brain, you have got to get the fuck out of here. You see what you see on TV or magazines or online and you think, why, that must be the place where people are making the Great Art! Clearly none of it lives here, so it must be hiding out in the institutions and social scenes of places with tall buildings and coastlines. But then you get there, and you come to a new realization that disdain for the very idea of culture is not unique to the midwest, and that feeble and braindead works of art (as well as their eager consumers) are everywhere.

My desire to go to art school was exactly that kind of flight, but I need to be clear here—I am not saying that landscape paintings of the prairie or NASCAR night at small-town dive bars or whatever don’t count as “real culture.” I was ready to fight my many classmates who moaned about how they thought KCMO was tiny and bland and ugly compared to Atlanta or Seattle or whatever bigger-pond they gave up on to go to KCAI. I mean that I was raised Pentecostal, which gave me a drastically different upbringing from that of anyone I ever met at art school.

If you haven’t seen Jesus Camp, Pentecostals are a particularly insular protestant sect that leans heavily towards Christian mysticism. They believe in faith healings and speak in tongues and strongly reject most parts of culture that are not evangelically Christian. One of our many short-lived youth pastors told me there was no point in going to college, because she had done the math and knew Jesus was coming back in 2014. I wasn’t just “closeted”— I couldn’t choose what I wore or watched or listened to. The “real world” as I could access it consisted of the grounds of the high school and the church, always under the watchful eye of my sin-seeking parents or other adults who had no desire to pry open their white-knuckle grip on my life. My childhood art-diet consisted of whatever I could sneak under the radar of my parents’ disinterest, plus the occasional works that passed their standards for moral worth. I had never seen a sitcom, but I cleaned house at Youth Bible Quiz and I knew about Glenn Beck and Dave Ramsay and The Drudge Report.

To deal with this, I learned to keep my business to myself and spent every other waking minute telling lies to maintain the few precious pieces of forbidden culture that I had scrounged up. A borrowed issue of Shonen Jump under my mattress, a bootleg copy of American Idiot under my pillow, a single “best friend” (also an artist, also online) who mostly served as a punching bag for my constant rage and despair and random blurts of evangelical propaganda. I started fantasizing about killing myself at age 12, and the desire to die didn’t really leave me until after I hit 30.

When I encountered the emotion that I think others describe as “not feeling queer enough,” I understood this as the natural response to a desolate void in my experience. Right when criticism of pop culture’s obsession with depictions of queer suffering began to ramp up, I arrived at art school with nothing but suffering, and it wasn’t even the interesting kind. I didn’t deal with homophobic bullies because I didn’t come out. I didn’t have tragic stories of working through fraught feelings about sex because I was repulsive to every entry on my long list of crushes, and I had never been allowed to date anyway. I didn’t have stories of being bashed in the locker room, just the empty ennui of having never felt like a person. I knew before I left home that the evangelical version of God wasn’t real, but I was still afraid of hell.

When I got to KCAI, I had been set up to fail. Art school wasn’t about developing technical skill or honing creative insight— it was about expressing yourself and finding your voice, but I had no voice and nothing to express that anyone would want to hear. I found out that the things I liked and knew about might not be sinful, but they could still be problematic or just weird nerd shit that nobody cares about. I didn’t know how to “be a creative” because I had long since stopped engaging with my own interests and interiority. I didn’t have a history to draw from— I hated everything that I came from, I wanted so badly to leave the before-times behind me and never look back. Make art from that? Absolutely not. I couldn’t risk making bad art even for my own private sketchbooks because being good at art was the only thing that made me worth the air I breathed. I still don’t really make anything I’m not paid for, not without chest-pounding anxiety every moment the pen is in my hand— it’s too vulnerable, and people have always been too cruel.

I had put all of my stock into art school because it was my only chance to smoothly slam the eject button on a life that was going to kill me with despair, but it was more of a lateral move at best. I just went from one vindictive, demanding culture to the next. So I avoided studio and phoned in projects that didn’t teach me anything I wanted to learn, for professors whose opinion of me ranged from “smart but lazy” to “arrogant jackass who just gets a kick out of questioning my authority.” When women who said they loved justice and equality told me that nobody wanted to see more art about depressed white boys from the suburbs, or sad stories about gays who don’t make us look happy and normal, I took it to heart. It turned out that no matter where I went, the people who told me they were better and smarter and there to guide me to the truth treated me like idiot scum who needed to be taken down a peg because I couldn’t just shut up and work. My classmates couldn’t seem to understand why I was always so angry.

It’s been eight years since I graduated. I have never stopped being angry, and I still don’t know how to make art. What I needed from an art education was not a personal brand or years of practice at cranking out an editorial illustration in a few hours, but a compelling philosophy for why it was worth it for me to make art at all. For a guy who puts a lot of effort into formal concerns, I don’t believe in the sublime. “Expressing your creativity” or “making something pretty” are not a compelling reasons for me to make something, nor is “having fun”— art is not fun for me, it is a compulsion. A stressful tic that is also the only worthwhile labor I am capable of doing. I am not interested in creating gay cottagecore kitsch or sexy anime pinups or whatever bland dogshit I can put in a hashtag this week to help Instagram sell adspace for betterhelp. Truly, deeply, from the bottom of my heart: all of that can get fucked. But still, I want to make things, and I want the things I make to be beautiful.

What I have always needed to know is that hell isn’t real and that it’s not a sin to be bad at work, that it’s legal to make art that most people don’t like or understand. Its fine— good, even— to feel bored and annoyed by the dull, bloated culture of illustration and animation and “content” that late capitalism has left us with. I needed to be told that the things I was good at and the things I had been through could be combined into something with actual meaning, that the accumulation of my experience was something worth putting onto the page, and then be taught how to do those things. I needed ways to connect the dots so that the precious specks of culture I had reached for and hidden and protected could be related back into the conversation that is Art. But that is not what art school is for.

In 2020 I moved away from KCMO to Chicago and finally satisfied my jealousy for experience. After much wailing and gnashing of teeth, I sort of taught myself how to hustle. Now I know that my own influences have value, and it is fine to approach art not as a child chasing the next set of jangling keys, but as a craftsman who has more to say than “everyone is valid.” My tattoo apprenticeship didn’t work out, but I finally have stood on my own two feet enough that I can have inklings of ambition again. It’s been almost a year since I finally told both of my parents to never speak to me again, and it was the best thing I’ve ever done for myself. I am always slowly picking up pieces and filling in holes.

I found Sufjan and read Something That May Shock And Discredit You and I realized that even if I hated the church, my cultural background in the metaphor and iconography of the Bible could still be part of the things I make. I found Lou Sullivan’s diaries and realized that I didn’t have to pretend my life before transition didn’t exist, I could reframe my own teen girlhood as a natal stage of faggotry. I got to see a Jess Dugan show at the Kemper Museum and cried my eyes out— but not as hard as I cried when I watched We’re All Going To The World’s Fair, or read the part of My Three Dads that’s about the ghost who haunted the last house I lived in before I left KC. They are a part of the world and so am I, and maybe if their art is worth making, then mine could be, too.

My experience was never really a void, it was just a life that no one wanted to understand or sympathize with. And I mean, how could they? Since I left home for college, I have met dozens-if-not-hundreds of trans people online and in person, but I have never met another person anywhere who grew up in the same kind of church I did. Not a single one. If it’s true that there are ten million Pentecostals in America, they outnumber trans people six times over. But people who grow up in that cage don’t leave. They don’t go to art school, they don’t become anarchists, and they certainly don’t transition.

Maybe that would be worth making art about. Maybe I’ll get around to it sometime before I die.

Would you mind saying more about "Encouraging us against locating our own taste in the context of our influences is the opposite of what I needed from art school. No one is an island, and nothing is ever 'just pretty'"? It's most intriguing.

The self-critical aspiring screenwriter who’s worrying about “the job” of it all, currently typing on this keyboard, can’t begin to express how close to home this essay hit, man. Ugh. Thank you💚